nightwaves beyond the marshlands

It had been six months since we’d left our tiny mountain town nestled in the valley of the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina. Not by choice, of course. But because this year the world fell apart—and is falling further still. I would have been perfectly content to sit at my writing desk and work on the book I’d been engulfed in for the last three years, but I finished it back in March. 103,000 words. 389 pages. Thousands of hours writing and revising. Complete. Now what? My husband Perry said we should celebrate, but I knew there would be no celebrating. We were barely allowed to leave our home. I fought every day to keep my single thread of peace from unraveling.

I watched my yard come to life with spring. The heirloom irises I planted bloomed black and deep purple, white and goldfinch yellow; soft flowers the color of wine. The air smelled of lemon mint and fennel from the ever-growing herbs that spilled from my flowerbed. I wandered the forgotten trails through the mountains under a green-leaved sky and swam in the clear bone-chilling rivers, counting wild mushrooms and red-tailed hawks, and wondered, how long will traveling be a forbidden concept? When will I be allowed to see the ocean again?

Summer came, the stay home order had lifted, and I spent my days sprawled out on my porch in the sun listening to the wind in the trees with my eyes closed, imagining the sound of the leaves rustling was the ocean within my reach. I planned a trip to Clearwater Beach, Florida, but the hurricanes came and so did the thunderstorms and those plans fell back into the ever-familiar territory of yearning.

It was two days before September and I refused to let summer go without dipping my toes in the ocean. I didn’t worry about the weather. I didn’t plan. I only thought of the sea and the sand and the sound of the gulls in the wind. Throwing our swimsuits in our backpacks along with our books, a stack of polaroid film, our cameras, and our toothbrushes, we made the five-hour drive to Hilton Head Island, South Carolina. The island is the largest barrier island on the southern Atlantic seacoast and is known for preserving the natural areas. There is an ordinance in place that governs how the buildings are situated among existing trees, making for the most beautiful canopy of green almost everywhere you go. Their ecological focus made it the ideal choice for us as it allowed us to explore the marshes, coastline, tidal pools, and natural forests throughout the Lowcountry away from crowds and the current plight that is the human existence.

When we arrived the air was warm and wet like one of those summers when the atmosphere always feels like rain. I ran down the path of white sand lined with sea oats blowing in the salt breeze—past the rows of blue umbrellas stacked on top of each other, disappearing into the cloudless sky of Coligny Beach—and I didn’t break stride until the soles of my feet were wet. The water washed over my sand-covered toes, a comforting warmth like the bath Grandma would draw for me when I was a child. Perry weaved his fingers into mine and we held hands in the sea. I rested my face, already sticky with salt, on his shoulder and we didn’t speak. With nothing but the sound of the ocean between us we swayed to the rhythm of the water and I felt the world and all its worries pull away from me. For just this one moment can we pretend everything is okay?

We stayed at the Sonesta Resort nestled along the coast, surrounded by tropical gardens hung with Spanish moss and lagoons with alligators lurking at the water’s edge. The stay was half off—maybe because of the hurricanes or maybe because of the pandemic. We didn’t ask, but there weren’t many people there. Everyone wore masks indoors and there were hand sanitizing stations in the lobby, by the elevators, and throughout the halls. I saw a toddler wearing a mask, his baby afro flowing from under the straps around his tiny ears. I wondered, does he understand why his face needs to be covered? Sweet little love. I wanted to kiss his chubby little feet and tell him that the world wouldn’t always be like this. I wanted to tell him that it would get better, but I couldn’t because I didn’t know how to lie to a baby.

We ate pineapple and jalapeño pizza by the pool and drank salt-rimmed peach margaritas. Rivers of chlorine ran down our shoulders from our hair and the sun-soaked concrete warmed our wet feet. A raven sat over our shoulder on an orange towel draped over the chair, waiting for a piece of crust. Some say a raven is a bad omen or a symbol of loss. Maybe they’re right as so much has been lost this year. But I liked the company of the giant bird and the way its black feathers reflected the sky. An openness. Or maybe a better word would be endlessness. Everything all at once all the time, an endless cycle of loss and uncertainty. I climbed into Perry’s pool chair and buried my face in his curls, breathing in the scent of sun and kissing the sugary salt from his mouth.

The clouds rolled in where the sun used to be and we watched lightning spark over the ocean. I waited for rain, but she never came. The beach turned dark with the moon behind storm clouds and we lost the coastline. Orange and red lights shined in the distance from the beach decks of fancy houses in an act to protect the sea turtles. The female loggerhead turtles come onto the shore to bury their eggs and their hatchlings use reflected light from the moon to guide them to the sea at night. Artificial white light can confuse them, stranding them in environments that aren’t their own. I gazed off into the orange glow and wondered, what are we guided by? Maybe the past. Or is it a fear of the future? Maybe it’s hope. A hope for a better future. Hope. I rolled the word around in my mind, smoothing its sharp edges. But it still felt too dangerous, too vulnerable to speak out loud.

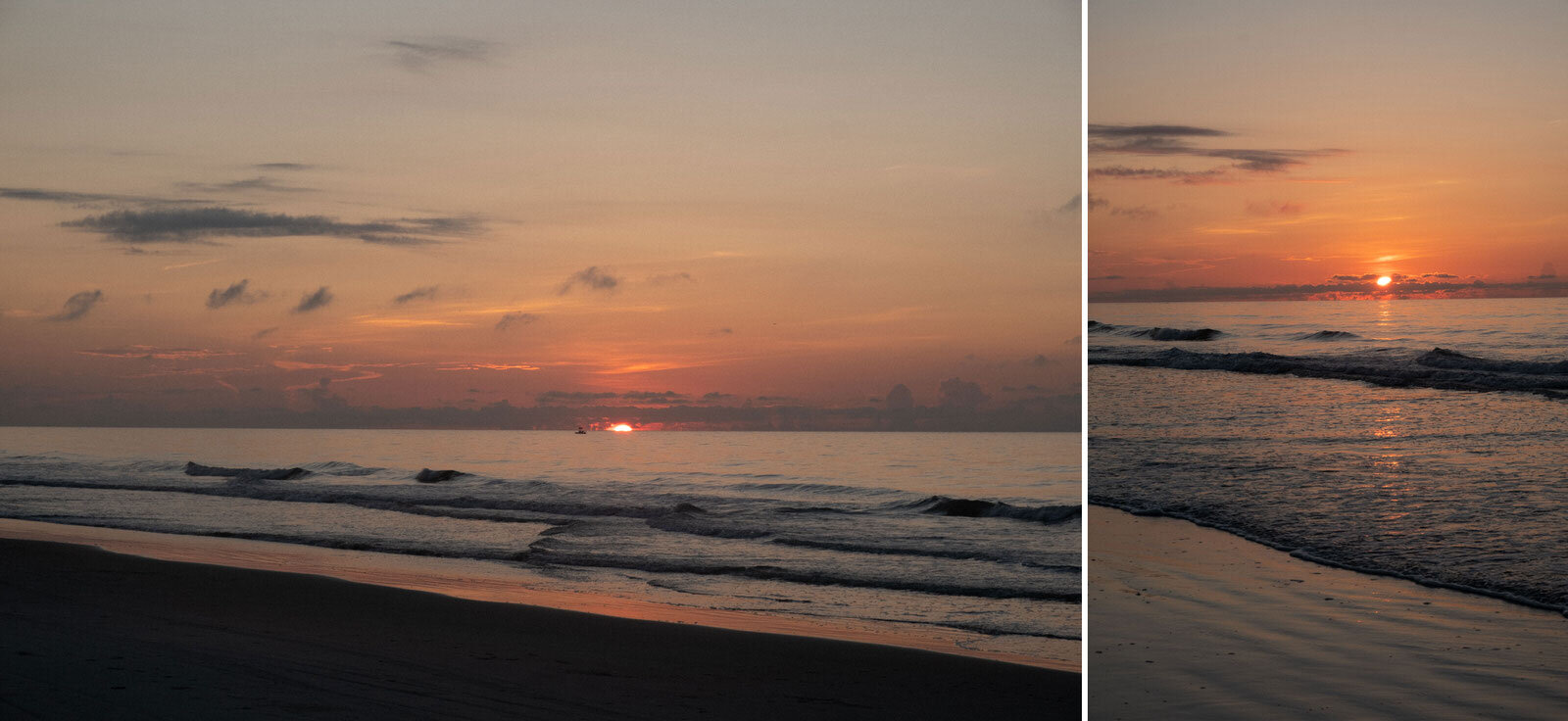

The next morning we woke when the sky was still black so we could watch the sun rise over the ocean. Curving along the lagoons we headed toward the palm trees on the horizon. They stood up against the bluing dawn like guardians to the sea and we followed the swaying of the sea oats until we reached the sand. Growing up in California, the only sunrise I ever saw was over the parched mountains or the cracked earth of the desert. When I went to college off the coast, I’d find myself in the cold morning sand—drowning in an oversized sweatshirt—waiting for the sun to come up. I’d crave its warmth on my face, but in the west the new day is always behind you.

The sunrise in South Carolina bathes your face in the purest pink light; it felt like a cleansing. The heat from my coffee cup spread through my palms and I watched the new day sun melt into the sea. We stretched out in the warm air and cuddled in the sand, waiting for the smoldering dawn to go from pink to gold and then from gold to white. I heard the jingling sound of a dog collar and laughed at the sight of a chocolate-colored Labrador running through the waves. He splashed the shoreline with the pink morning tide and licked my face. I thought, this is what joy looks like. Dogs are our link to everything good, the simple pleasures of being alive—joy externalized. I put my fingers through his salt-crusted fur and kissed his wet nose.

When the sun turned white, we took a water taxi through the marsh canals to the island of Daufuskie. The cordgrass and estuary reeds rubbed alongside the edges of the boat and I had to hold back from reaching for them, feeling them whip against the tips of my fingers. The sea air undressed me in the wind, untying my dress and pulling the braids from my hair. Perry’s bandana that he wore as a mask unraveled from around his neck and we had to turn around for it. I watched him drop his long arms into the water over the side of the boat and pull up the salt-drenched fabric. He wrung it out on the deck and flashed me a smile. I spotted more dolphins that I could count and shot my hands in the air with excitement at every one. Watching the sea birds glide in and out of the canals and wade by the murky edge, I envied them. The blue herons in their majestic stillness and the egrets in their delicate grace, fully existing in the present moment. Why must we always be doing, thinking, yearning, needing, worrying? I wanted to be like the quiet, wild birds of the marshlands. But see, there I go wanting again. There I go yearning to be something other than what I am.

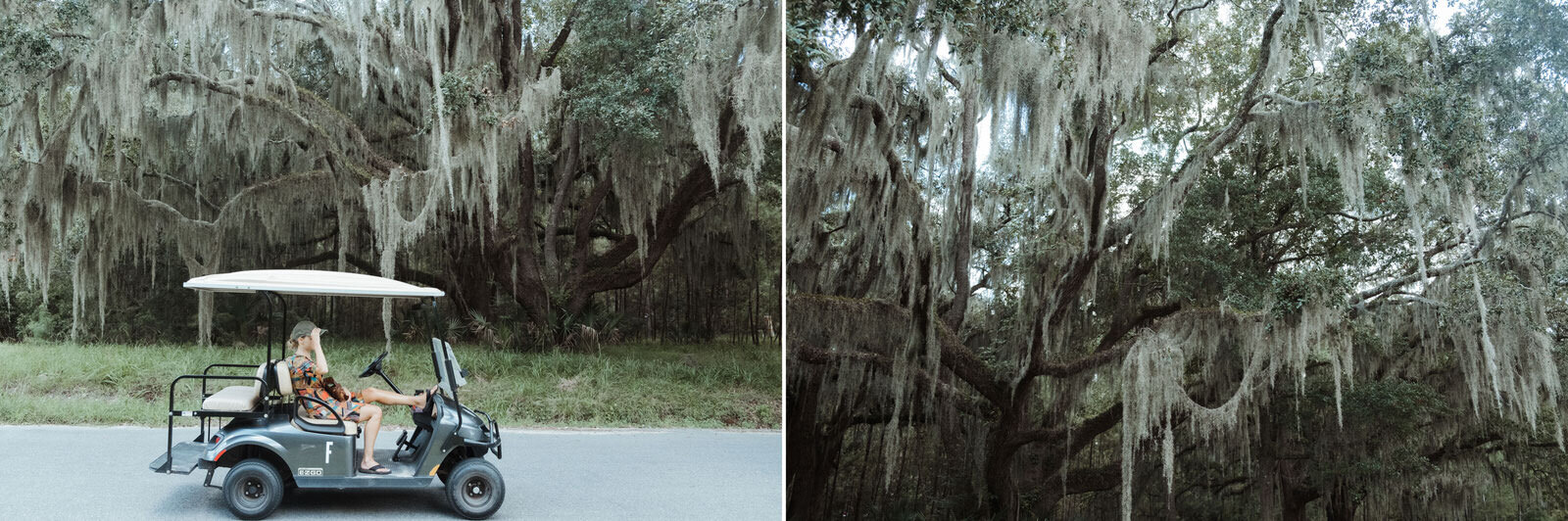

Daufuskie Island can be described as “paradise beyond”—without a bridge to the mainland, and only a few paved roads, the island is steeped in a simpler time. Surrounded by the waters of Calibogue Sound, it is the southernmost inhabited sea island in South Carolina and is only five miles long. Daufuskie comes from the Muscogee language and means “sharp feather”, for the island's distinctive shape. The shape of birds, I found a special kind of freedom on the island. White sand beaches, ancient live oaks cloaked in Spanish moss, and the eclectic arts scene filled me with a Lowcountry mystique that I could feel in my bones.

The residents and guests of Daufuskie use golf carts and bicycles to travel around the island. We rented a golf cart and weaved in and out of dirt roads; pointing out deer, armadillos, and a bald eagle. Stumbling upon a farm, we parked the cart even though the sign said Closed. A woman came out of a tiny wooden shack with pixie-cut gray hair that dripped sweat and created a wet halo around her neck. I asked if I could pet the animals and she said sure, for a donation. So we gave her all the cash we had and I pet a calico-colored goat named Jewel. She had a twin sister named Precious who was cream white and shy; I was slow to stroke her velvet ears.

After the farm, we made our way through the maze of backroads until we saw a swaying of blue in a world of green. Hand dyed textiles—vintage silks and organic cottons—colored blue with natural indigo blowing in the warm island breeze. We stopped and talked with the artist. I smudged my fingers in the blue leaves while I listened to her share the delicate process of indigo-dying. She noticed the hand carved rings that lined my fingers and when I said we carved them she said we could make a good living on the island. A simpler life scrolled through my mind—coffee by the sea, an old house with wood floors that creaked and walls lined with books, watching the moon rise over the ocean, sleeping under tangled strands of moss, and falling asleep to the night-sounds on the island. I stared down at my hands stained with indigo and thought, maybe a life with less brings a fulfillment that’s otherwise unaccessible? A life where the focus is on living and creating and nothing more.

When we arrived back to the mainland, I saw a boat with “Daddy’s Girl” written across the side. I took a picture and sent it to to Dad. “That’s what we need, little girl,” he said. I smiled against an aching in my chest because I knew that even if we had a boat or all the freedoms of the universe, Dad would never leave his little nowhere town of Michigan; working a job he hates, numbing the pain of being alive with bad action movies and guilt-ridden religion. I slid my phone into my pocket and tried to keep the free spirit of the island with me.

Back at the beach, we spread out in the white powder sands and it covered my body like a second skin. The sound of the sea, the gulls, and the cicadas—a world trilling with life, with freedom. I watched a little boy in a cowboy hat play catch his dad and I squinted past the rows of blue umbrellas to a little girl running to the shore with a white pail, never breaking stride; just like I did at the first sight of the ocean upon our arrival. Full of childlike wonder, these are the things worth holding onto. Why is it so hard to hold onto the things that bring us joy? Maybe I’m holding on too tight. Suffocating all the life out of living. A crab peeked out of his hole, scanning for threats, only to disappear again. So many threats. But wait, is this what freedom looks like?

I followed paw prints in the sand until I reached the water. I felt the earth sinking beneath my feet and a flash of Dad the last time he came to visit shot through my mind. It was last year when I still recognized the world we live in. Salt water crept up the long black dress that I’d found in a thrift store in a town I can no longer remember. Dad held my hand over the big waves like I was still a little girl who needed saving. I felt myself smiling at the thought of my hand in his giant calloused palm and the sound of his big laugh and my heart exploded and ached in the same moment. I wondered, did I ever need saving? I was used to being the one doing the saving.

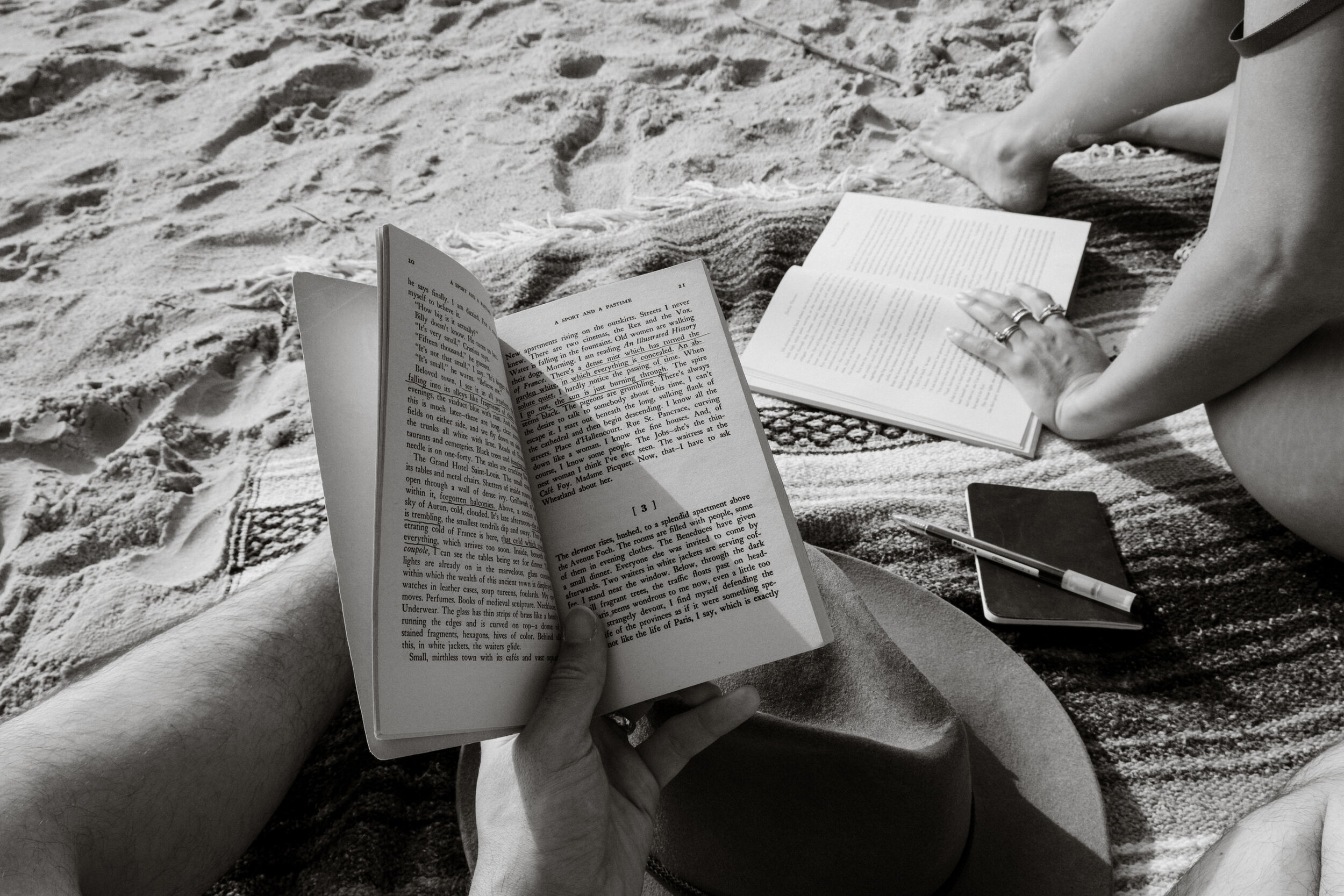

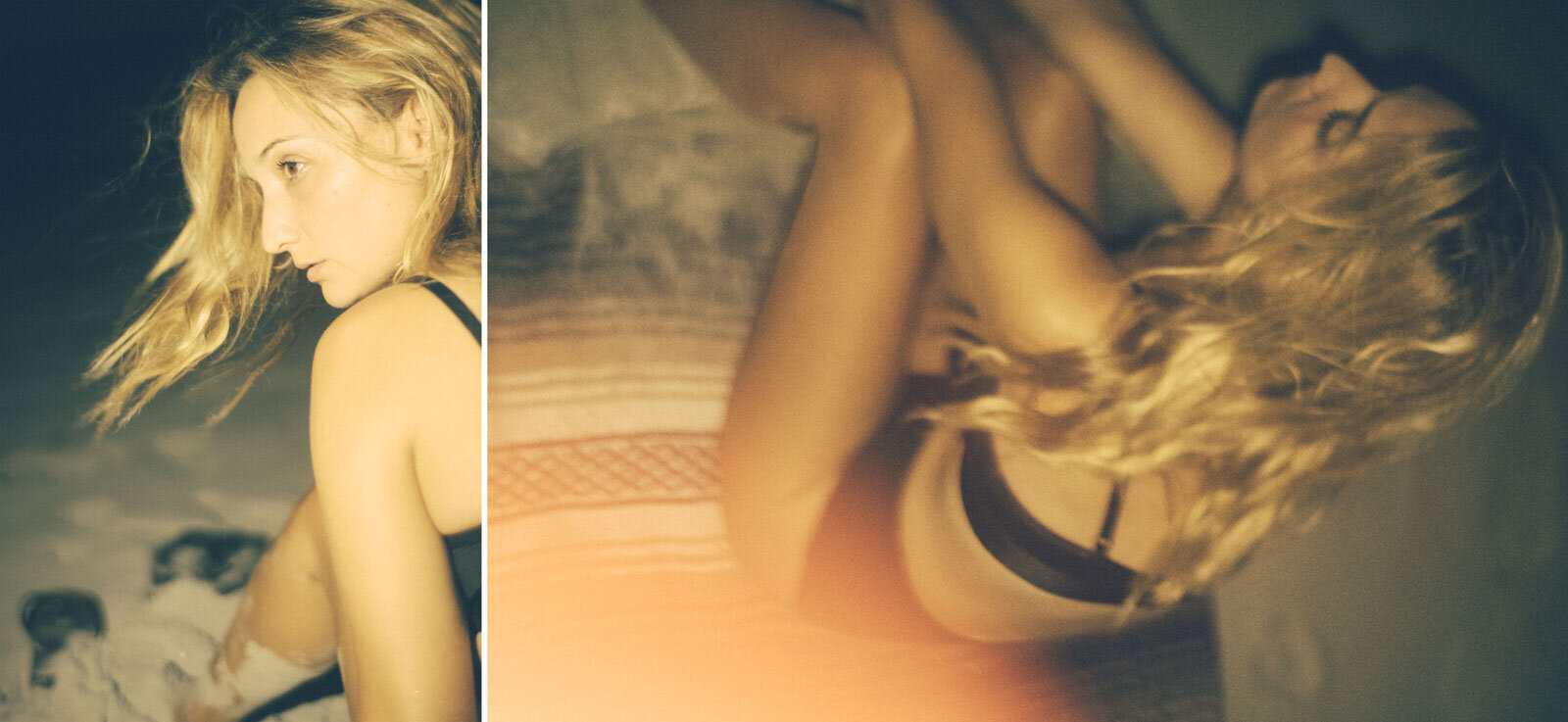

We sprawled out on a Mexican blanket that we bought at a gas station outside Albuquerque, New Mexico and I listened to the tall grass sway in the wind on the dunes. Drinking a green juice, the paper straw dissolved in my mouth and I thought about the chocolate chip cookies we ate in bed last night; fucking in the king size sheets I felt the crumbs against my thighs.

I peered at Perry, his black curls dusted with silky white sand. The sun glinting off the water behind him, he held James Salter's A Sport and a Pastime in his hands. I laid my head in his lap and felt the sun scorching my heels. My elbows has been rubbed raw from propping myself up against the beach, reading and marking the sentences from my book; dragging my pen against the grit, I felt it catch along the word “loneliness.” We read the underlines in our books out loud until the sun fell behind the palmettos. Perry read, “I am at the center of emptiness. Every act seems purer for it, easier to define. The sounds separate themselves. The details all appear.” I listened to the sound of his voice—deep as the sea floor—and thought, living is in the details.

I waited for the moonrise and brought my book overhead. I squinted against the sand that fell from the pages and licked my lips, the taste of salt-scented air had collected in the cracks. Rubbing the sand from my eyelashes, I listened to the stories of the night waves and grasped for calm and for power from the ocean as it can be two opposing things at once. The cotton candy moon filled the space over the sea and I pointed out Saturn and Jupiter and Vega in the distance; trying not to think of all the things I needed to do when we head back to the mountains. So many things—they began to mount in my brain, stacking higher with each thought. But that’s not why I’m here. I’m here to forget all the things I need. I’m here to exist as if this is the only moment and it is not in my nature to need so much. But can we ever escape our need? I don’t know, but I’m going to try.